My current project is about internally heated convection where there's a volumetric heating/cooling source. More details to come in the future.

Liquid Crystals

In summer of 2019, I worked with Professor Franziska Weber on liquid crystals. You've likely interacted with liquid crystals without even knowing it - an LCD screen is a Liquid Crystal Display. A liquid crystals is an inbetween state - it's sort of a liquid and sort of a solid. In a liquid, all the particles are randomly aligned while in a solid, all the particles are completely aligned. For a liquid crystal, we can think of the particles as being "vaugely aligned." Now that we understand that, we can move on to the physical model of the liquid crystals we used.

Given a large splotch of liquid crystals, we can look at a very tiny portion of it and see in general which direction all the particles in that portion are facing. We can identify this direction with a unit vector $n$ which we call the director. What we desire is to model this director at every point in the liquid crystal and see how it changes as we evolve in time. Thus, we have that $n$ is dependent on both space and time - $n(x,t)$. One may notice that a vector has an inherent direction but the liquid crystals themselves don't and thus a vector pointing in the direction $-n$ would also be equally valid. This symmetry that is apparent with the director must be preserved by any model we use for liquid crystals. A model that does that is the Q-tensor model.

Given a director $n(x,t)$ we can define a Q-tensor

\[ Q(x,t) = s(x,t) \left( n(x,t) n(x,t)^T - \frac{1}{d} I_d \right) \]

where $d = 2,3$ is the dimension of the space we are dealing with and $I_d$ is the identity matrix of dimension $d \times d$. The $s(x,t)$ function is what's called a scalar order parameter which is a scalar valued function that gives an idea of how well a patch of liquid crystals are aligned. The idea behind the Q-tensor is we encode the director into $Q$ and then evolve it in time. Thus if we want to know the director at any point in the splotch of liquid crystals or at any later time, we can find the Q-tensor at that space/time and decode the director (by finding the eigenvectors). The model we used to evolve the liquid crystals is governed by the following equations:

\[

\begin{cases}

&Q_t = M\mathcal{H} \\

&q_t = P(Q): Q_t

\end{cases}

\]

where

\[

\begin{cases}

&P(Q) := \frac{aQ - b(Q^2 - \frac{1}{2}tr(Q^2)I) + c tr(Q^2)Q}{\sqrt{2\left(\frac{a}{2}tr(Q^2)-\frac{b}{3}tr(Q^3)+\frac{c}{4}tr^2(Q^2)+A_0\right)}} \\

&\mathcal{H} = L_1 \Delta Q + \frac{L_2+L_3}{2} \alpha(Q) - qP(Q) \\

&\alpha(Q) = \sum_{k=1}^d (\partial_{ik} Q_{jk} + \partial_{jk}Q_{ik}) - \frac{2}{d} \sum_{k, \ell=1}^d \partial_{k \ell} Q_{k \ell} \delta_{ij}

\end{cases}

\]

The above equations are for the evolution of liquid crystals with no flow and also satisfy a certain energy constraint:

\[

\begin{equation} \frac{d}{dt} \frac{1}{2} \int_{\Omega} L_1 | \nabla Q|^2 + (L_2+L_3) |\nabla \cdot Q|^2 + r^2 dx = -M \int_{\Omega} |H|^2 dx \end{equation}

\]

We were able to jump off some pre-existing research for semi-discrete schemes of this same system to develop and implement a fully discrete scheme (which I will not describe or discuss here). We showed analytically that our proposed method was energy stable (preserving the above energy constraint in a discrete sense) and also convergence of the method.

This is a rough sketch of what I worked on to get my Master's Thesis (I worked on the energy stability part) and also got some of it into a paper: arXiv:2012.00278

Dynamics of the Inextensible Inverted Flag with Piston-Theoretic Forcing Term

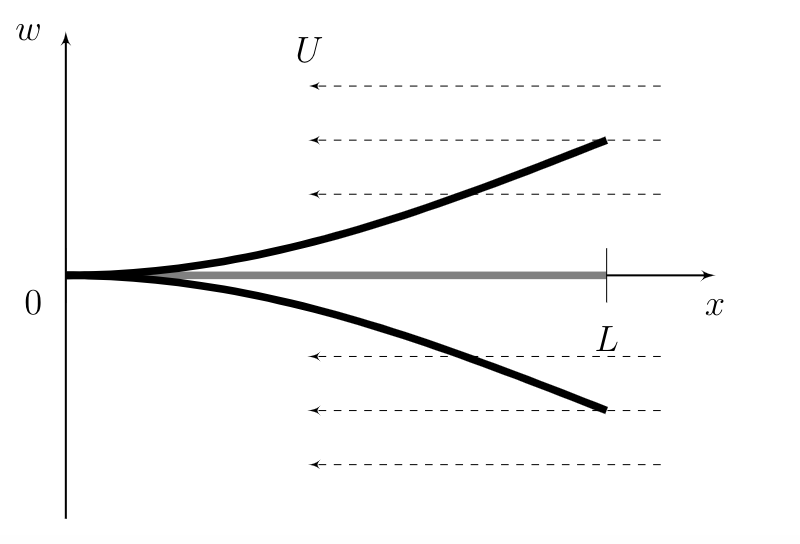

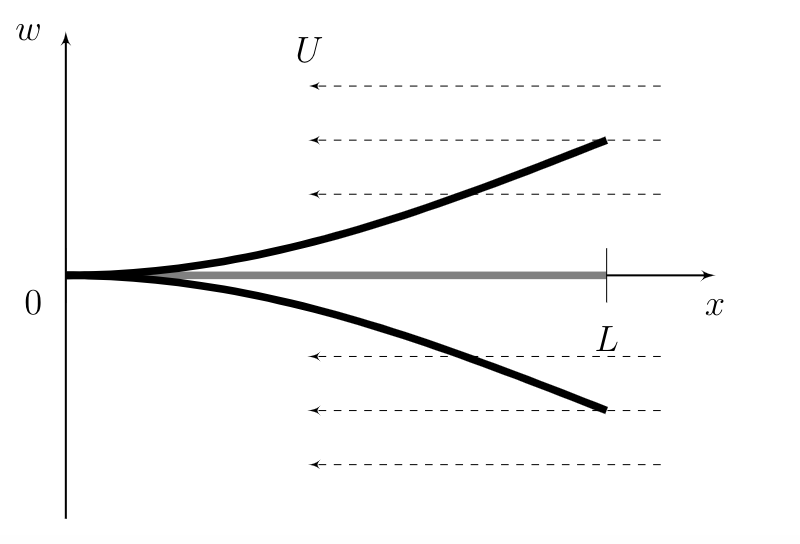

In summer of 2019, I worked with Professor Jason Howell on the inverted flag system funded by a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) at CMU. In the inverted flag system, a thin metal beam is fixed on one end and free to move on the other. Fluid flows from the free end to the fixed end, inducing motion in the beam. The model is of current interest in several applications, including the design of piezolectric harvesting devices. See below for a figure of the system.

The beam is of length $L$ and the fluid flows at speed $U$. A full model of the system would involve a system of PDEs with Navier Stokes for the flow of the fluid coupled with another equation for the motion of the beam. This however is computationally and mathematically expensive. Engineers who look at this system have use tools from Piston Theory which simplifies the interaction between the fluid and the beam to derive just a single equation which models the motion of the beam. We looked at the model proposed by Dowell and McHugh for the inextensible inverted flag - that is a model which preserves the arclength.

\[ \begin{cases}

w_{tt} +\mathbf{A}(w)(x,t) = -\beta(w_t - Uw_x) & \text{in } (0,L) \times (0,T)\\

w = w_x = 0 & \text{in } \{0\}\times (0,T) \\

w_{xx} = w_{xxx} = 0 & \text{in } \{L\} \times (0,T) \\

w(0) = w_0(x), w_t(0) = w_1(x) & t=0, x \in [0,L] \\

\end{cases} \]

\[ \begin{align}

\mathbf A (w) =\underbrace{-D\partial_x\big[(w_{xx})^2w_x \big]+D\partial_{xx}\big[w_{xx}\big(1+(w_x)^2\big)\big]}_{\text{nonlinear stiffness}} \\[1 ex]

+\underbrace{w_x\left[-\int_0^x\left((w_{x t})^2+w_{x tt}w_{x}\right) d\xi\right]}_{\text{nonlinear inertia}}\\[1 ex]

+\underbrace{w_{xx}\int_x^L\Big[\int_0^{\xi_2} \big((w_{x t})^2)w_{x tt}w_{x}\big)d\xi_1\Big]d\xi_2}_{\text{nonlinear inertia}}-

\end{align}

\]

To finally model the system compuationally, we conducted a modal analysis where we found an orthonormal basis of modes (also called shape functions) such that the shape at any single time could be written as a linear combination of these modes.

\[ w(x,t) = \sum_{i=1}^n q_i(t) s_i(x) \]

The time dependent coefficients $q_i(t)$ are found through an infinite system of ODEs. To actually conduct numerics for the system, we truncate the system to finitely many, $N$, equations

$$m \left[ q_j'' + \sum_{i=1}^N \left[q_i''(q_i)^2+(q_i')^2q_i\right]\mathcal I_{iiij}\right] + D q_j k_j^4 + D \sum_{i=1}^N q_i^3\left[\mathcal S_{iiij}+\mathcal S_{jiii}\right] = -\beta q_j' + \beta U \sum_{i=1}^N q_i \gamma_{ij}$$

This is just the $j^{th}$ line of the system of ODEs. This is a second order, nonlinear, and implicity system of $N$ equations which through a reduction of order produces a system of $2N$ equations. Using MATLAB's inbuilt $\texttt{ode15i}$ ODE solver we could then solve numerically for the $q_i(t)$ and then take the linear combination with the shape functions to recover a numerical system to the PDE.

We found in our results that a certain regime of behavior known as flutter where the beam oscillates periodically was not found. It is known that the inverted flag in real life actually does flutter, but it seemed that our simulations were unable to capture it. However, we did see a certain bifurcation point where as we varied the flow speed, $U$, that the beam would change from damping to equilibrium to reaching a nontrivial deflected state. Further, this bifurcation point appeared to be independent of the initial condition. When the beam reached the nontrivial deflected states, there were contributions from multiple modes, not just a single mode. Finally, we also saw that the modal simulations were unable to conserve the inextensibility condition. We saw that the arc length was not conserved for certain regimes of $U$ and $\beta$. Here's a simulation demonstrating the system approaching a deflected state:

Here's me at my favorite spot in the computer lab that summer doing research.